1987. This was the year that black metal

truly started to sound like black metal as we know it today. It was also

the year I was born, so I feel a particular affinity to the albums from

this year. But don't think that means I'm going to rate them unfairly.

Oh, no. These albums can stand on their own.

One of the problems that I've run into with 1987 (and it continues from here on out) is that I wasn't able to find release dates for many of the albums, aside from the year. So when I don't have a month for the album release, I'll go with the month it was recorded, if I can find that out. If I can't figure that out either, I'll just stick it at the end of the year after I've done everything I have dates for. That's the best I can manage.

Sometimes,

bands are able to crank out album after perfect album, year after year

(Darkthrone's string of 92-95 comes to mind). Sometimes, bands are

better off taking a break from that kind of release schedule and taking

the time to dig deep within the music. For Quorthon, this was definitely

the case. After putting out albums in 1984 and 1985, as well as

appearing on both Scandinavian Metal Attack compilations,

Bathroy took a break from the studio in 1986. Then they exploded back

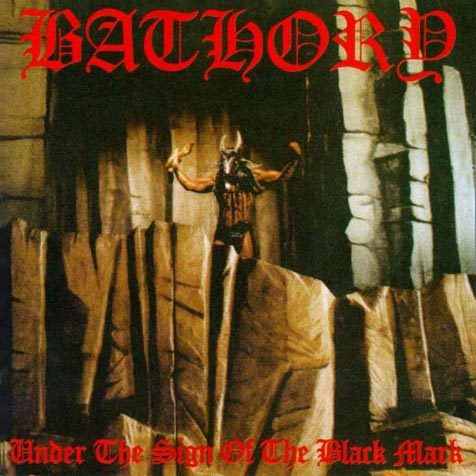

onto the scene with this absolute monster. The rather goofy cover

(especially compared to Bathory) might make you think that Under the Sign of the Black Mark would be cheesy, like some kind of "eviler than thou" Man O' War. Oh, you would be so wrong.

Sometimes,

bands are able to crank out album after perfect album, year after year

(Darkthrone's string of 92-95 comes to mind). Sometimes, bands are

better off taking a break from that kind of release schedule and taking

the time to dig deep within the music. For Quorthon, this was definitely

the case. After putting out albums in 1984 and 1985, as well as

appearing on both Scandinavian Metal Attack compilations,

Bathroy took a break from the studio in 1986. Then they exploded back

onto the scene with this absolute monster. The rather goofy cover

(especially compared to Bathory) might make you think that Under the Sign of the Black Mark would be cheesy, like some kind of "eviler than thou" Man O' War. Oh, you would be so wrong.

By this point, Quorthon had shed most of the weight of a band, realizing that he had no intentions of playing live with Bathory. He handled all the strings himself, effectively making the band a duo (although Christer Sandström is credited on the album for bass, it's unclear what tracks he actually appears on). Stefan Larsson, who did skin duty on the first two Bathory albums, was out, and Paul Lundberg was in. And although this would be the only album he would record, he did a damn fine job. He didn't have the pure furious energy of the Brazilian drumers (Igor "Skullcrusher" Cavalera and D.D. Crazy in particular), but he had a much more powerful presence on the kit than Larsson. Whether laying down a solid groove for epic "Enter the Eternal Fire" or slamming it full speed on "Massacre," Lundberg's snare rings out true through the mix. It's a very splashy sound that contrasts sharply with the more blended snare of The Return or Bathory, and while his blasts aren't as speedy as some other drummers, they have teeth-gritting solidity to them that I love. Larsson often sounded like he was struggling to match Quorthon's tempos. Lundberg's style says "I could do this all day."

Quorthon himself has improved everything. His guitar playing is tight and focused, with none of the "flailing" feel of Bathory. Songs like "Chariots of Fire" have a furious tremolo attack that doesn't wear down or get distracted. The improvised guitar solos (which Quorthon admits he never practiced) are all rip-roaring, finger-shredding monsters—not the kind of solos you would sit down and learn note-for-note, but the kind of solos that make you thrash your limbs around in a frenzied air-guitar mayhem. One of the standout tracks, though, is the mid-tempoed "Enter the Eternal Fire." This song hints at where Quorthon plans to go next with the band, but it's still a throughly "black metal" track—one that will be a clear influence on bands like Immortal. Again, Quorthon's lyric writing abilities have only gotten stronger (although he hasn't yet reached the summit), with even the ode to Elizabeth Bathory ("Woman of Dark Desires") being a complex piece of poetry, and Quorthon delivers everything with an uncompromising snarl that I wish I could channel when I work on my own project.

The one other extremely important thing that Quorthon did on Under the Sign of the Black Mark is introduced keyboards (which he himself played) into the black metal vocabulary. There's not really a lot to say about it, other than that they are there, and they add to the music, giving the album a full sound that doesn't need to be taken up by excess reverb. But most importantly, they mean that when bands like Emperor and Dimmu Borgir (re) introduce keyboards to the black metal sound in 1994, they are not "killing" or "perverting" the TRVEKVLT sounds of black metal as defined by some group of uncompromising arbiters of "the real black metal sound." We'll talk more about that when we get to those bands, but I wanted to point out that it started here, with Quorthon.

Quorthon would be back in 1988 with Blood Fire Death and a whole new sound, which is, arguably, "not black metal." On the other hand, Blood Fire Death and Hammerheart are fantastic albums, and I will be covering them when I get there.

Final Verdict: 9/10 - Quorthon changed the game with this relase, and set a high bar for Scandinavian black metal that wouldn't be met for at least five years (and some say ever). This is the height of Bathory's black metal days.

One of the problems that I've run into with 1987 (and it continues from here on out) is that I wasn't able to find release dates for many of the albums, aside from the year. So when I don't have a month for the album release, I'll go with the month it was recorded, if I can find that out. If I can't figure that out either, I'll just stick it at the end of the year after I've done everything I have dates for. That's the best I can manage.

Bathory - Under the Sign of the Black Mark (May, 1987)

Sometimes,

bands are able to crank out album after perfect album, year after year

(Darkthrone's string of 92-95 comes to mind). Sometimes, bands are

better off taking a break from that kind of release schedule and taking

the time to dig deep within the music. For Quorthon, this was definitely

the case. After putting out albums in 1984 and 1985, as well as

appearing on both Scandinavian Metal Attack compilations,

Bathroy took a break from the studio in 1986. Then they exploded back

onto the scene with this absolute monster. The rather goofy cover

(especially compared to Bathory) might make you think that Under the Sign of the Black Mark would be cheesy, like some kind of "eviler than thou" Man O' War. Oh, you would be so wrong.

Sometimes,

bands are able to crank out album after perfect album, year after year

(Darkthrone's string of 92-95 comes to mind). Sometimes, bands are

better off taking a break from that kind of release schedule and taking

the time to dig deep within the music. For Quorthon, this was definitely

the case. After putting out albums in 1984 and 1985, as well as

appearing on both Scandinavian Metal Attack compilations,

Bathroy took a break from the studio in 1986. Then they exploded back

onto the scene with this absolute monster. The rather goofy cover

(especially compared to Bathory) might make you think that Under the Sign of the Black Mark would be cheesy, like some kind of "eviler than thou" Man O' War. Oh, you would be so wrong.By this point, Quorthon had shed most of the weight of a band, realizing that he had no intentions of playing live with Bathory. He handled all the strings himself, effectively making the band a duo (although Christer Sandström is credited on the album for bass, it's unclear what tracks he actually appears on). Stefan Larsson, who did skin duty on the first two Bathory albums, was out, and Paul Lundberg was in. And although this would be the only album he would record, he did a damn fine job. He didn't have the pure furious energy of the Brazilian drumers (Igor "Skullcrusher" Cavalera and D.D. Crazy in particular), but he had a much more powerful presence on the kit than Larsson. Whether laying down a solid groove for epic "Enter the Eternal Fire" or slamming it full speed on "Massacre," Lundberg's snare rings out true through the mix. It's a very splashy sound that contrasts sharply with the more blended snare of The Return or Bathory, and while his blasts aren't as speedy as some other drummers, they have teeth-gritting solidity to them that I love. Larsson often sounded like he was struggling to match Quorthon's tempos. Lundberg's style says "I could do this all day."

Quorthon himself has improved everything. His guitar playing is tight and focused, with none of the "flailing" feel of Bathory. Songs like "Chariots of Fire" have a furious tremolo attack that doesn't wear down or get distracted. The improvised guitar solos (which Quorthon admits he never practiced) are all rip-roaring, finger-shredding monsters—not the kind of solos you would sit down and learn note-for-note, but the kind of solos that make you thrash your limbs around in a frenzied air-guitar mayhem. One of the standout tracks, though, is the mid-tempoed "Enter the Eternal Fire." This song hints at where Quorthon plans to go next with the band, but it's still a throughly "black metal" track—one that will be a clear influence on bands like Immortal. Again, Quorthon's lyric writing abilities have only gotten stronger (although he hasn't yet reached the summit), with even the ode to Elizabeth Bathory ("Woman of Dark Desires") being a complex piece of poetry, and Quorthon delivers everything with an uncompromising snarl that I wish I could channel when I work on my own project.

The one other extremely important thing that Quorthon did on Under the Sign of the Black Mark is introduced keyboards (which he himself played) into the black metal vocabulary. There's not really a lot to say about it, other than that they are there, and they add to the music, giving the album a full sound that doesn't need to be taken up by excess reverb. But most importantly, they mean that when bands like Emperor and Dimmu Borgir (re) introduce keyboards to the black metal sound in 1994, they are not "killing" or "perverting" the TRVEKVLT sounds of black metal as defined by some group of uncompromising arbiters of "the real black metal sound." We'll talk more about that when we get to those bands, but I wanted to point out that it started here, with Quorthon.

Quorthon would be back in 1988 with Blood Fire Death and a whole new sound, which is, arguably, "not black metal." On the other hand, Blood Fire Death and Hammerheart are fantastic albums, and I will be covering them when I get there.

Final Verdict: 9/10 - Quorthon changed the game with this relase, and set a high bar for Scandinavian black metal that wouldn't be met for at least five years (and some say ever). This is the height of Bathory's black metal days.

No comments:

Post a Comment